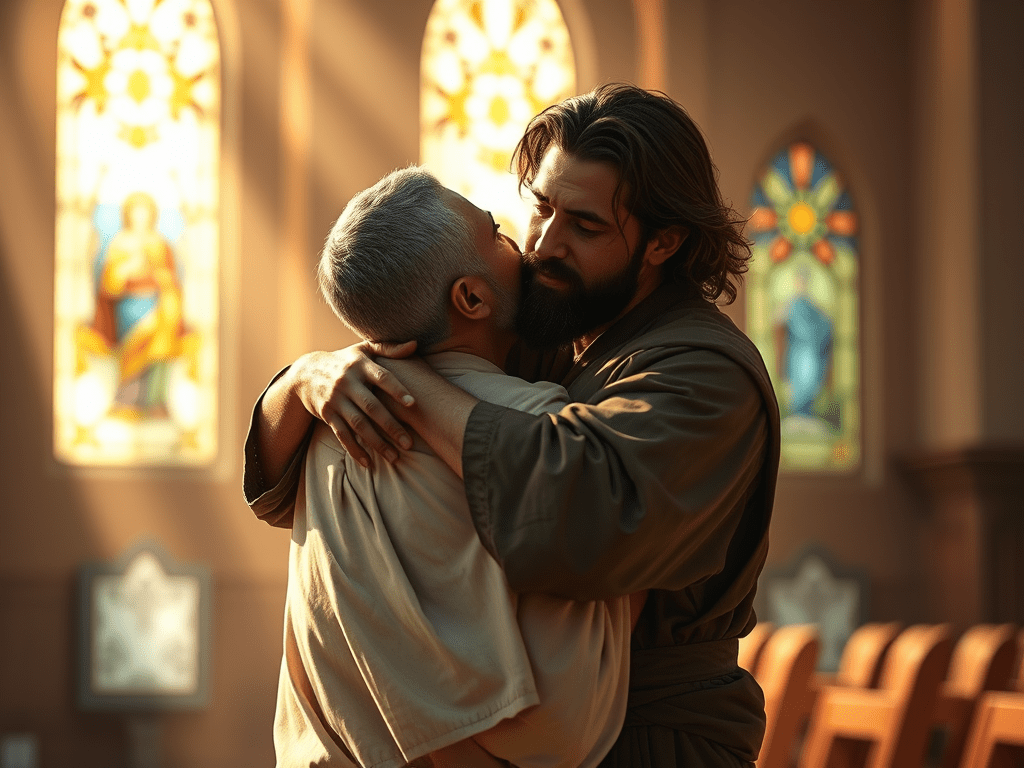

The Beauty of the Gospel in Brokenness

In nearly every church across the globe, one can sense the scars of division—strained relationships, misunderstandings, unresolved grievances, and even lingering bitterness. These fractures are not new to the life of God’s people. From the first century, the body of Christ wrestled with the challenge of living out unity in a broken world. Yet in the midst of this reality, God gives us a precious gem in Scripture: the brief but profound Letter to Philemon.

In this personal letter, the Apostle Paul pleads with Philemon to welcome back his runaway slave Onesimus—not as property, but as a brother in Christ (Phlm 1:16). This appeal is not simply about social justice or reform; it is fundamentally a display of the gospel at work. Paul’s request underscores the transformative power of Christ’s love, which transcends societal norms and cultural barriers. The transformation that occurs in the heart of Onesimus exemplifies the new creation we become in Christ (2 Corinthians 5:17).

As believers, we are called to reflect this reconciliation in our own lives. The story of Philemon and Onesimus challenges us to consider how we view those who have wronged us or have walked away. Are we willing to extend grace, forgiveness, and acceptance, mirroring the unconditional love that Christ demonstrated?

The Letter to Philemon not only provides comfort but serves as a divinely inspired model for reconciliation. In our contemporary context, we face myriad opportunities to embody Christ’s reconciliation. Whether it’s within our congregations, families, or communities, there is a calling to act in love, mediation, advocacy, and servanthood leadership. Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God” (Matthew 5:9). This beatitude reminds us that peacemaking is not just a passive state but an active pursuit of God’s kingdom on earth.

Moreover, reconciling relationships in the church is integral to living out the gospel. In Ephesians 4:1-3, Paul urges believers to “walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.” This passage encapsulates the essence of our mission as the church—to embody Christ’s reconciliation.

In embracing this call, we can confront the divisions within our communities, fostering an environment of compassion and understanding. May we strive to be conduits of God’s grace, offering forgiveness, healing, and hope as we navigate the brokenness around us. In doing so, we not only honor the message of Philemon but reflect the heart of our Savior, who is in the business of restoring all things to Himself.

Reconciliation Through Christian Love

At the heart of Paul’s appeal lies Christian love. Love is not something we manufacture; it is God’s eternal attribute, planted in us through the Spirit. As John reminds us, “We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19). Miroslav Volf describes God’s love not merely as an activity but as His very essence: “God’s very being is love, not just what He does” (Volf, God Is Love, p. 30). This divine love, revealed most clearly in Christ’s sacrifice, reconciled us to God. Paul explains: “While we were enemies we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son” (Rom 5:10). Jacob Arminius reflects on this profound truth by affirming that God’s just love is satisfied in forgiving sinners through punishing sin upon His Son (Pinson, Criswell Theological Review 18.2, 2021, p. 33).

If we are reconciled to God, then two virtues naturally follow: love for God and love for neighbour. The Shema (Deut 6:4–6) and Christ’s teaching (Mark 12:30) command us to love the Lord with all our being. Bernard of Clairvaux rightly observed that true love of God is “not merely acknowledging His benefits but responding to His infinite goodness” (On Loving God, pp. 19–21). Scripture also repeatedly calls believers to love one another (Lev 19:18; John 15:12–13). The Apostle John warns, “If anyone says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar” (1 John 4:20).

Philemon embodied both virtues. Paul commends him: “I hear of your love and of the faith that you have toward the Lord Jesus and for all the saints” (Phlm 1:5). His love refreshed the hearts of the saints (1:7). Longenecker notes that Philemon’s love and faith “were directed toward Christ, yet expressed for the sake of fellow believers” (Longenecker, Philippians and Philemon, p. 226). Paul himself models love in his appeal. He could have commanded Philemon but chose instead to entreat him “for love’s sake” (Phlm 1:9). As Villiers explains, Paul’s persuasion flows not from mere rhetoric but from “his deep conviction in Christ’s love” (Tolmie & Friedl, Philemon in Perspective, p. 270). Without Christian love, reconciliation is impossible. Love is not sentiment but sacrifice—choosing the good of the other above self. If God so loved us when we were guilty, how can we withhold forgiveness from one another?

Reconciliation Through Christian Mediation

Sometimes wounds run too deep for direct reconciliation. Pride, pain, or fear can create barriers. In such cases, the role of a Christian mediator becomes vital. In Philemon, Paul steps in between Philemon and Onesimus as a mediator. His action reflects Christ, the ultimate mediator: “For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim 2:5). Colin Gunton insists that the church’s mediating role must always “reflect Christ’s work alone” and never be seen as autonomous (Gunton, “One Mediator…,” Pro Ecclesia 11.2, 2002, p. 149).

Paul’s appeal was not only practical but theological—rooted in the gospel’s power to reconcile enemies. In Phlm 1:8–9, Paul appeals with love, not authority. In 1:16, he redefines Onesimus’s identity: “no longer as a slave but more than a slave—as a beloved brother.” Torrance draws a striking parallel: just as God mediated covenant reconciliation with Israel, Paul now mediates reconciliation in the household of faith (The Mediation of Christ, pp. 13–28). When conflicts divide, God may call us to step in—not as judges, but as mediators of grace. Mediation requires humility, prayer, and the courage to reflect Christ’s peace (James 1:5; Matt 5:9). Who in your church needs you to stand in the gap?

Reconciliation Through Christian Advocacy

Mediation is one side of Paul’s role; advocacy is the other. Paul not only mediated but also defended Onesimus before Philemon. Like Christ, who is our Advocate with the Father (1 John 2:1), Paul identifies with Onesimus, calling him “my child” and “my very heart” (Phlm 1:10, 12). Lucas notes that Paul’s advocacy works because he identifies Onesimus with himself (The Message of Colossians & Philemon, p. 151). Even more, Paul offers to bear Onesimus’s debt: “If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account” (Phlm 1:18). This echoes Christ, who bore our sins in His body on the cross (1 Pet 2:24). Luther compared Paul’s advocacy here to Christ’s self-emptying, “leaving all heavenly rights for the sake of redeeming sinners” (Phil 2:7).

Copenhaver reminds us that advocates often pay a personal cost: “The mediator often becomes everyone’s target, but Paul is willing to endure such shame for the sake of the church” (Copenhaver, JETS 63.4, 2020, p. 21). Gordon affirms that Christian advocacy is part of the church’s mission, confronting injustice and restoring relationships (Gordon & Evans, The Mission of the Church and the Role of Advocacy, pp. 12–13). To advocate means to stand with the guilty, to shoulder their shame, and to intercede for their restoration. Are we willing, like Paul, to say, “Put it on my account”?

Reconciliation Through Servanthood Leadership

Finally, Paul models servanthood leadership in reconciliation. Though he had apostolic authority, he chose to appeal with humility: “Though I am bold enough in Christ to command you… yet for love’s sake I prefer to appeal” (Phlm 1:8–9). This reflects Christ, who came “not to be served but to serve” (Mark 10:45). Paul saw himself as a servant (δοῦλος) for the sake of the church (1 Cor 9:19). Clarke explains that Paul voluntarily enslaved himself for the church’s wellbeing (A Pauline Theology of Church Leadership, p. 99). Yang Tan adds that Paul’s servanthood arose from his obedience to Christ and his conviction that “giving is better than receiving” (Full Service, p. 55).

True reconciliation requires leaders to embody humility, vulnerability, and prayer. Hammer advises leaders to remember that their authority is God-given stewardship, not self-promotion (Servant Leadership, pp. 54–55). Paul shows this in his prayerful intercession for Philemon (Phlm 1:4–6) and his shared leadership with co-workers (1:23–24). Tan further stresses that shared leadership produces wisdom and unity (Shepherding God’s People, pp. 116–117). Leaders are most Christlike not when they command but when they serve. Reconciliation flourishes when leaders embody humility, sacrifice, and prayerful vulnerability.

Will We Bear the Cost?

The book of Philemon is not a quaint relic; it is the Spirit’s living word to the church today. It challenges us: will we love enough to forgive? Will we mediate like Paul, advocate like Christ, and lead with servanthood? The witness of the gospel demands nothing less. Paul bore Onesimus’s debt. Christ bore our sin. Shall we not bear one another’s burdens (Gal 6:2)?

The call is clear: if the church is to shine as the reconciled body of Christ, we must embrace reconciliation as love in action, mediation in humility, advocacy in sacrifice, and leadership in servanthood. Only then will the church embody her true calling: to be a living testimony of God’s reconciling grace in Christ Jesus.

The next time conflict threatens to divide your fellowship, open the book of Philemon. Read Paul’s words slowly, prayerfully, and personally. Then ask: Lord, where are you calling me to love, mediate, advocate, or serve?

Jonathan Samuel Konala M.Tech.,MTh

Leave a comment